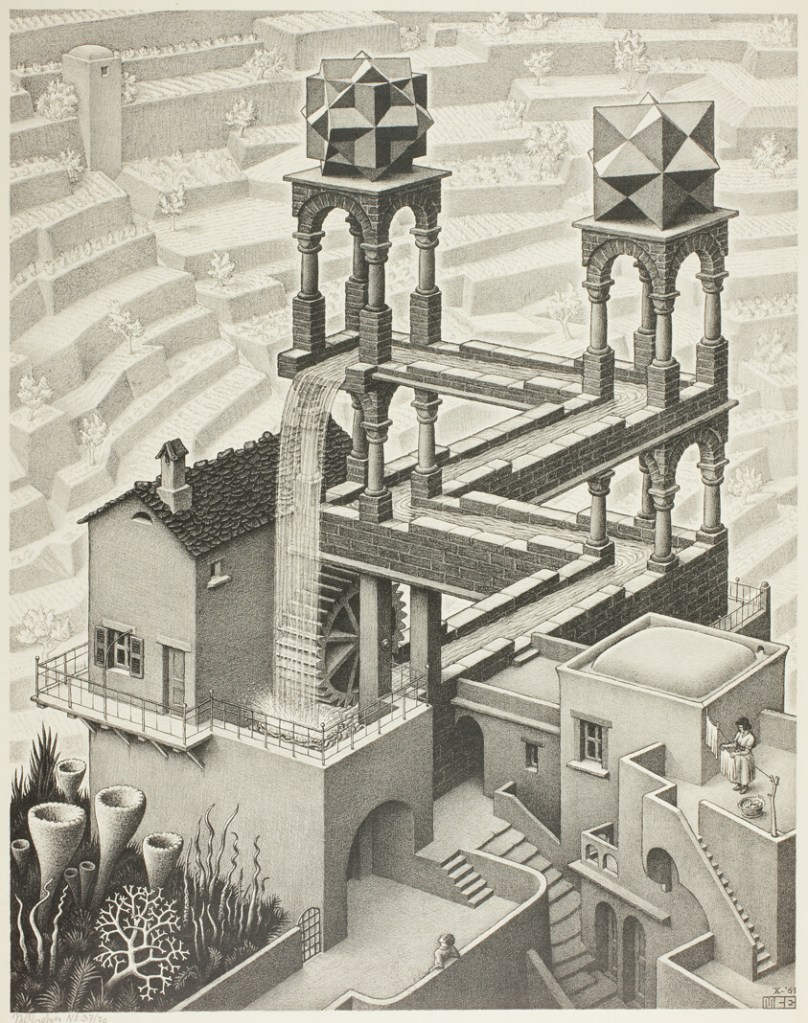

Escher’s Waterfall is unsettling to me. A perpetual cascade of water whose origin and end are indistinguishable. Water forever falling and returning, causality suspended in an optical illusion. This impossible structure haunted me as I wrote my article “Causal Loops, Ontological Crises, and Customary International Law”, now published in the German Yearbook of International Law. The painting’s endless cycle captures the paradox at the heart of customary law, where obligation and practice feed one another in an unbroken loop.

I had the privilege to share these reflections at the Law and Popular Culture event in Maastricht University Faculty of Law in 2024. There, I spoke of how the law of the sea, and especially UNCLOS, lives within such cycles. Custom is not an abstract puzzle; it is the hidden current that binds States even when they deny its force.

The relevance of this discussion is renewed with the current debates over deep seabed mining. The United States, under Trump’s leadership, claims to stand outside UNCLOS (due to the US having not ratified UNCLOS and, so, asserting a freedom from its constraints). Yet the reality is more complex. Much of UNCLOS has become customary law. As such, its core obligations—including those shaping the governance of the ocean’s depths—bind all States, regardless of formal ratification.

Thus, the Escherian loop is not mere empty philosophical prattle. It is the ground upon which real disputes are contested. As the United States seeks to chart a path circumventing the law of the sea, it is anchored in the same cycle.

In this, the law of the sea teaches us that social reality is not always a matter of signatures, but of group practice and enduring belief (or collective recognition). A lesson as relevant in the politics of deep seabed mining as in the paradoxes of art.

Click Here to read the article (Open Access).

Special thanks to the conveners of the Law and Popular Culture event, Agustin Parise, Arthur Willemse, Eline Couperus, and Livia Solaro. And my deepest gratitude to Kenneth Chan, the editing team, and the anonymous reviewers of the German Yearbook of International Law.